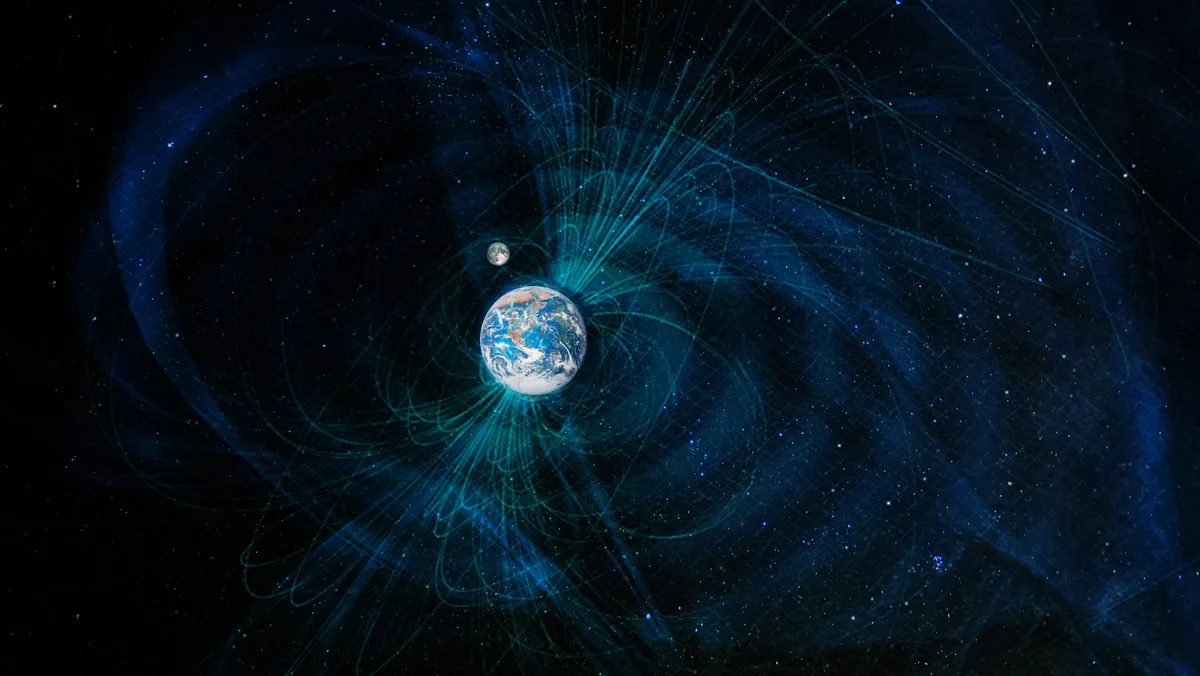

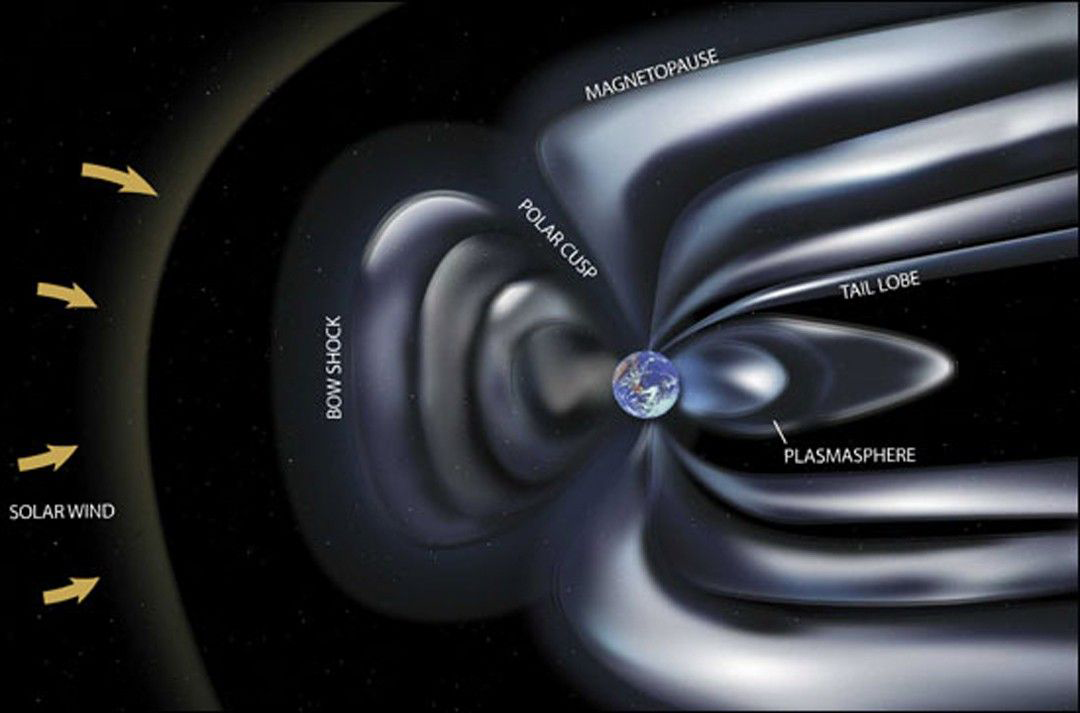

Think of Earth’s magnetic field as its invisible force field, shielding us from the Sun’s charged particle onslaught (aka the solar wind). This magnetic shield isn’t just floating around magically—it’s powered by a geodynamo, which is basically Earth’s molten metal lava lamp in the outer core. The swirling, churning mix of molten iron and nickel down there generates electric currents, and boom! We get a planetary magnetic field.

Think of Earth’s magnetic field as its invisible force field, shielding us from the Sun’s charged particle onslaught (aka the solar wind). This magnetic shield isn’t just floating around magically—it’s powered by a geodynamo, which is basically Earth’s molten metal lava lamp in the outer core. The swirling, churning mix of molten iron and nickel down there generates electric currents, and boom! We get a planetary magnetic field.

Earth’s magnetic field is like a giant cosmic bouncer, keeping most of the solar wind’s rowdy charged particles from crashing the party. If not for this protective shield, these particles would gradually tear apart our ozone layer—the very thing standing between us and a UV-ray barbecue. One way this happens is when solar winds snatch up bits of atmospheric gas, stuffing them into magnetic field bubbles before yanking them away like a cosmic claw machine. Scientists studying Mars found that when its magnetic field ghosted, the planet’s atmosphere practically packed up and left with it—turning Mars into the dry, dusty place it is today.

Now, if you imagine Earth as a giant bar magnet, it’s kind of wonky—tilted about 11° off from its rotational axis. But here’s the real plot twist: what we call the North geomagnetic pole is actually the South pole of Earth’s magnetic field, and vice versa. So, when your compass points north, it’s technically pointing toward a magnetic South! Confusing? Yeah, magnets like to keep things mysterious.

Now, if you imagine Earth as a giant bar magnet, it’s kind of wonky—tilted about 11° off from its rotational axis. But here’s the real plot twist: what we call the North geomagnetic pole is actually the South pole of Earth’s magnetic field, and vice versa. So, when your compass points north, it’s technically pointing toward a magnetic South! Confusing? Yeah, magnets like to keep things mysterious.

Now, if you’re wondering how we know all this, enter paleomagnetism—basically, the Earth’s diary of its ancient magnetic field. As lava cools into rock, it locks in the planet’s magnetic history like a time capsule. And guess what? The magnetic field flips now and then, leaving behind zebra-stripe patterns on the seafloor. These reversals don’t just make for cool geological records—they help scientists date rocks, track the prehistoric shuffle of continents, and even sniff out hidden metal deposits. So yeah, Earth’s magnetic field isn’t just a force field—it’s also a time machine, a treasure map, and a planetary security system all rolled into one.

Now, if you’re thinking we can predict where this is all going—think again. Earth’s magnetic field is about as predictable as a cat’s behavior. Measuring it over a few years, decades, or even centuries doesn’t give us a clear long-term trend because it’s always doing its own thing, going up and down for reasons we still don’t fully understand. Also, the field isn’t just a simple dipole (like a bar magnet)—it’s got a lot more complexity, so even if one part weakens, the overall field might not actually be shrinking. Wherever you are on Earth, the planet’s magnetic field can be thought of as a 3D vector—kind of like GPS coordinates but for magnetism. The classic way to check its direction? Grab a compass and find magnetic North. But here’s the catch: magnetic North doesn’t always line up with true North, and the angle between them is called declination (D)—basically.

Now, if you’re thinking we can predict where this is all going—think again. Earth’s magnetic field is about as predictable as a cat’s behavior. Measuring it over a few years, decades, or even centuries doesn’t give us a clear long-term trend because it’s always doing its own thing, going up and down for reasons we still don’t fully understand. Also, the field isn’t just a simple dipole (like a bar magnet)—it’s got a lot more complexity, so even if one part weakens, the overall field might not actually be shrinking. Wherever you are on Earth, the planet’s magnetic field can be thought of as a 3D vector—kind of like GPS coordinates but for magnetism. The classic way to check its direction? Grab a compass and find magnetic North. But here’s the catch: magnetic North doesn’t always line up with true North, and the angle between them is called declination (D)—basically.

Oh, and Earth’s magnetic north pole? It’s been on the move. Back in the early 1900s, it was drifting at about 10 km (6.2 miles) per year from Canada toward Siberia. By 2003, it had picked up the pace to 40 km (25 miles) per year, and it’s been speeding up ever since. At this rate, it might just pack its bags and head off on a world tour!